In the midst of the Great Depression, farmers on Colorado’s eastern plains also had to contend with another problem, the Dust Bowl. It was the worst ecological disaster in the history of our state.

Farmers began moving to the arid regions of the Colorado plains after the passage of the Homestead Act in 1862. By 1909, the best homestead lands had been claimed, so Congress enlarged the Act, allowing homesteaders to claim double the number of acres if they were willing to try dry farming methods. But this land wasn’t meant to be plowed. Before the land had been farmed, the plains had been covered with native grasses. When extreme drought conditions hit in the 1930s, however, there was nothing left to hold down the dry topsoil. As a result, southeastern Colorado and neighboring states suffered enormous dust storms that blacked out the sun and fell to the earth in drifts like snow. Farms were literally blowing away. Baca, Prowers, Las Animas, and Kiowa counties were hardest hit in Colorado, but the storms were so large that dust fell as far away as the East Coast!

It wasn’t just the drought and dust storms, either. Farm prices dropped, and many families were starving. Cattle couldn’t find enough to eat, so thousands had to be killed. And the small amounts of crops that farmers were able to grow were ravaged by grasshoppers and other pests. 1936 and 1937 were particularly bad years, and many farmers packed up and left. Colorado Farm and Ranch Population Changes in 1937, a publication from the Colorado Experiment Station, noted that the state’s farm population that year was “less than it has been at any time since 1920 and represents a decrease of 5.6 per cent since 1930 and 4.0 per cent since 1935.”

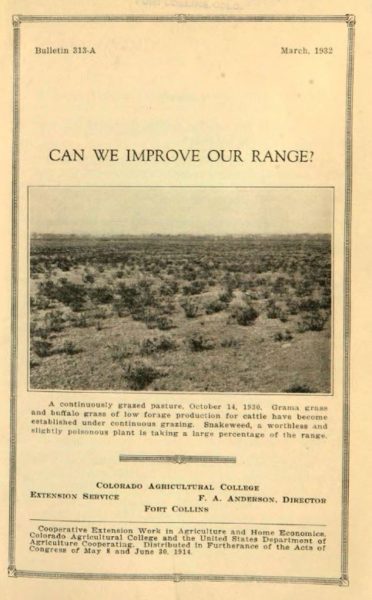

It became clear that dry farming was not sustainable and that something needed to be done to conserve the soil. New Deal programs provided jobs and relief to impoverished farmers, and the federal government also worked to develop new farming techniques. Here in Colorado, the Agricultural Experiment Station (part of the Colorado Agricultural College, today’s CSU) sought to educate farmers and ranchers on improving their land. They issued pamphlets and bulletins like Soil Blowing and Its Control in Colorado (1936); A Basis for Rating the Productivity of Soils on the Plains of Eastern Colorado (1938); Construction of Irrigation Wells in Colorado (1935); and Type of Farming Areas in Colorado (1935). Can We Improve Our Range? (1932) dealt with drought issues on range and grazing lands, advocating a “rotation system of grazing” so that lands had an opportunity to recover. Cattle Management for Improving the Range (1932) also considered overgrazing and “wasteful range practices.” Restoring Colorado’s Range and Abandoned Croplands (1940) was another pamphlet that provided farmers with useful techniques and information.

It became clear that dry farming was not sustainable and that something needed to be done to conserve the soil. New Deal programs provided jobs and relief to impoverished farmers, and the federal government also worked to develop new farming techniques. Here in Colorado, the Agricultural Experiment Station (part of the Colorado Agricultural College, today’s CSU) sought to educate farmers and ranchers on improving their land. They issued pamphlets and bulletins like Soil Blowing and Its Control in Colorado (1936); A Basis for Rating the Productivity of Soils on the Plains of Eastern Colorado (1938); Construction of Irrigation Wells in Colorado (1935); and Type of Farming Areas in Colorado (1935). Can We Improve Our Range? (1932) dealt with drought issues on range and grazing lands, advocating a “rotation system of grazing” so that lands had an opportunity to recover. Cattle Management for Improving the Range (1932) also considered overgrazing and “wasteful range practices.” Restoring Colorado’s Range and Abandoned Croplands (1940) was another pamphlet that provided farmers with useful techniques and information.

Researchers looking for primary sources documenting the Dust Bowl era in Colorado will find these and numerous additional resources in our library. The State’s official publication of annual agricultural statistics provides detailed data on the economic conditions of farming in Colorado. An audit of the Colorado Emergency Relief Administration (1936) relates to the Depression statewide, but contains sections on rural rehabilitation, drought relief, and aid to counties. Economic data can also be found in the Experiment Station’s report on Farm Tax Delinquency in Colorado, 1928-1936.

Analysis of Fifty Years’ Record of Meteorological Data, published by the Experiment Station in 1939, offers statistics and observations on precipitation during the era. The Experiment Station also published other research reports such as A Study of Farm Organization and Soil Management Practices in Colorado (1937); Preliminary Report on the Soils of Colorado (1937); and Soils of Eastern Colorado (1938). Accomplishments of the Colorado Experiment Station, distributed to state legislators in 1937, outlined research efforts in irrigation, range and pasture management, and other important issues. Meanwhile, the State Planning Commission published a Report on Land Resources of the Great Plains Area of Colorado (1936). Even schoolchildren were taught the importance of conserving the land. The state’s Department of Education issued A Bulletin on Conservation of Natural Resources to help teach students about conserving the land that they would one day inherit.

In 1939 the Experiment Station issued Colorado’s Farm and Ranch Population, which showed a slight recovery as the drought ebbed. The most significant recovery, however, came with the increase in prices and demand that resulted from World War II. The expansion of irrigation on the plains, especially with construction of the Ogallala Aquifer, helped put an end to dry farming. But there’s no guarantee that the water will always be there. Search our library’s online catalog to find publications about the State’s efforts to protect and conserve our water resources.

Finally, for a glimpse into the lives of the people who lived through the Dust Bowl, see Steve Leonard’s book Trials and Triumphs: A Colorado Portrait of the Great Depression, with FSA Photographs, available for checkout from our library or on Prospector.

- How to Spot the Differences Between Eagles and Hawks - August 16, 2021

- How Transportation Projects Help Tell the Story of Colorado’s Past - August 9, 2021

- Time Machine Tuesday: The Night the Castlewood Canyon Dam Gave Way - August 3, 2021