Listen to this article

Whether it concerns moments in Colorado’s local history or happenings in the national arena or on the world stage, the Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection (CHNC) offers a distinctly Coloradan point of view of America’s rich history. The joy of the CHNC collection lies in the surprising things you are sure to find at every turn, whether it’s the fantastic and strange advertisements promising cures for just about any ailment, articles and comic strips that display the shocking social mores of days past, or the unabashed (and in some ways familiarly modern) bias in news reporting…

Sometimes, though, it’s just plain fun to search for keywords and browse the results. Take impeachment as a window into history. As of writing, if you search the word “impeachment” in CHNC’s search engine, you will receive over 6,000 mentions in newspapers dating back to 1859; here’s a snap-shot of some of the highlights.

The Gold Regions

The earliest search result brings you to the front page of the August 20, 1859 edition of the Rocky Mountain News, and the Constitution of the State of Jefferson which is printed there in full. It begins:

We, the people of the Gold Regions of the Rocky Mountains, grateful to the Supreme ruler of the Universe for His blessing, and feeling our dependence upon Him for a continuation of the same, do ordain and establish a free independent Government by the name of the State of Jefferson…

The “State” then being established is what we now call the Jefferson Territory, a huge area of land which included – and was nearly double the size of – present-day Colorado. Although never formally recognized by the United States, it was the precursor to the Colorado Territory (established in 1861), which would eventually be admitted into the Union as the State of Colorado in 1876.

Impeachment is provided for in two brief sections of the proposed constitution:

§ 22: The House of Representatives shall have the sole power to bring the charge for impeachment,

§ 23: All impeachments shall be tried by the Senate, and while sitting for that purpose, the Senate shall be under solemn oath or affirmation to do justice according to law and evidence.

The constitution was rejected by a popular referendum in September of 1859.

Later by Telegraph

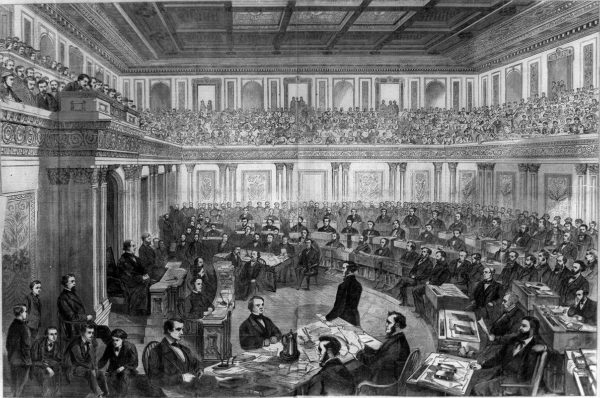

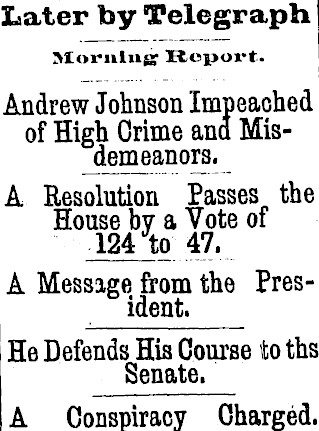

The front page of the February 25, 1868 edition of the Rocky announced the breaking news: “Andrew Johnson Impeached of High Crime and Misdemeanors” … “He Defends His Course to ths Senate” [sic]. Judging by the typo, you might imagine the scene: the type hurriedly being set, the giant press huffing and whirring ready for printing, uncertainty in the air as the first president in US history has been impeached. The high crime and misdemeanors in question was President Johnson’s unlawful removal of Edwin M. Stanton, the Secretary of War, from office.

The article goes on to relay the House proceedings – who voted for what – noting, “The democratic members attempted to resort to filibustering, but were cut off after an unsuccessful effort…”

Who Doubts that Justice Will Be Done?

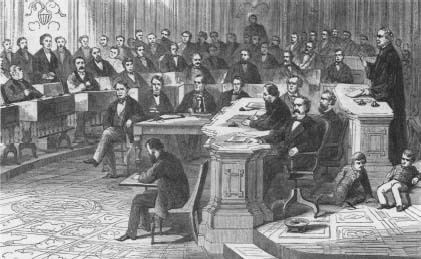

The March 7, 1868 front page of the Rocky reflects on Johnson’s impeachment and upcoming Senate trial with the dramatic flair peculiar to the journalism of the time:

In the senate a new scene is now opening. A high court of impeachment has been organized, the highest judicial officer of the nation presiding. Andrew Johnson will appear before them. The senators are the impartial judges, the house, in the name of the people, are his accusers. The senate chamber will wear all the sanctity of a court. Who doubts that justice will be done?

The author (attribution is not given) is quite clear in their position:

It is a common remark that the senate will not convict the president. We must differ from this opinion. It is a clear case, and we believe the senate cannot escape a verdict of guilty.

Biased though the author undoubtedly is, we are assured that it is for the Constitution that such bias leans: “When the president refuses to execute a law because he thinks it is unconstitutional, he not only violates it, but he usurps a power given to a co ordinate branch of the government.”

The article draws to a close and refers to the President almost like an already-condemned man: “We cannot see any escape for Mr. Johnson.”… “His fate is merited and deserved.”

Nearer Home

In the May 13, 1868 edition of the Rocky, there is an article titled ‘Impeachment and the State,’ written just before the Senate had made its verdicts on his conviction. “Elsewhere we have commented on the look of things at Washington,” it begins. “Let us regard for a moment the effect nearer home.” Were Johnson to be acquitted by the Senate, a major concern was that, “[Johnson’s acquittal] lessens the chances of Colorado’s admission into the union.” Regardless of the Senate’s ruling, the author was optimistic that “a new effort will be made in the same direction which cannot fail of success.”

How Long will it Take?

Since Andrew Johnson was the first US president to be impeached, how the Senate trial was going to proceed was a topic of speculation. A Daily Colorado Tribune article from March 15, 1868 states: “Those who imagine that the President can be impeached within thirty days are likely to be greatly disappointed.” And with good reason, says the author:

Certainly there must be no haste, no levity, no trifling with justice and candor in a tribunal and before an assembly so august, with a personage so august at the bar accused of ‘high crimes and misdemeanors.’

Without a real precedent, the author is obliged to remember “the most notable of [impeachment] trials” – that of Warren Hastings, the Governor-General of India from 1774-1785, when India was under British Empire rule: “[Edmund] Burke, in the name of the Commons of England, opened the charges in a speech which occupied three days.” Then, “after 148-days of Investigation and discussion, Hastings was acquitted by large majorities on each separate charge.”

Mercifully, as it turned out, it wasn’t quite as drawn out for Andrew Johnson; in May 1868, the Senate failed to gain the two-thirds majority required to remove a president.

A Little Over a Century Later

Over 100 years elapsed before impeachment was seriously on the cards for a president. Talk of President Nixon’s impeachment in the CHNC archives is much more localized than Johnson’s. For example, the University of Colorado’s November 14, 1973 edition of the student newspaper The Fourth Estate featured an article about an upcoming meeting discussing “the pros and cons of impeaching President Nixon.” The event was to be held at South High School in Denver and speakers would include an unknown person of “national prominence.”

Or look to the Steamboat Pilot’s October 25, 1973 edition where 50 residents were polled about the possibility of impeaching Nixon. Of those residents, only 2% believed that the President was “telling the whole truth to the American people,” while 54% of residents felt that his actions warranted impeachment.

The October 24, 1973 edition of The Aurarian has an article titled ‘Man on Street Favors Impeachment.’ The “man on street” was a sampling of the student population of the Metropolitan State College (now MSU). The comments from students are thoughtful, yet mostly condemning of the President’s actions. One student was particularly damning:

‘I’d like to see him (Nixon) go to jail,’ Lawson declared. ‘Nixon has been a gangster ever since he entered politics,’ the English major added.

*

Regardless of what you search for, you’re sure to stumble upon something of interest in the CHNC archives – all the more interesting with the added benefit of hindsight. The CHNC collection is constantly growing. We are regularly adding new windows through which you can glimpse history.

- 19th Century Colorado Feminist Newspapers, The Antelope and The Queen Bee - December 1, 2021

- Land Acknowledgements - November 30, 2021

- Announcing our Collaborative Conversations Cohort! - November 17, 2021